My Brief Romance With Advertising

I graduated from high school in 1961. The 60's were just getting underway. I'd read Keroac's On The Road and was soon to encounter Sartre and Existentialism. The conventions and strictures of the 50s had to go. Babbitt, all things boosterish, four-square, and button-down were held in contempt.

Fast forward thirty some years. I've succeeded in avoiding a career, the straight and narrow and, in spite of that-and without crime or dirty dealing-somehow I own my own home in the Bay Area. Any judicious person would say that luck had something to do with it. One day an acquaintance even called me a yuppie -- I'd just purchased a new Saab. Few comments had pleased me more.

The stage was nearly set for my brief romance with advertising.

I'd just completed another round of schooling, this time getting an M. A. in Clinical Psychology. And just as my earlier milestones in schooling had led apparently nowhere, this one followed suit-except for one thing. This time, I was forty-six—almost fifty. Did I really want to become a psychotherapist? How many productive years might I have left? Twenty-five, thirty? And what about this art thing—this stepchild of my life? My fervent, if fitful, excursions in that direction, first in poetry, later in painting, sculpture and photography had not yielded much. Over the years, I'd never been able to commit myself with real conviction to life as an artist. But here I was, and the abstract idea that my time was limited suddenly had become real. It sobered me up a good bit.

A decision was made. In the time left, I would give the art side of my life the best I could. Unbeknownst to me at the time, this would include a pas de deux with advertising. Here's how it came about. My new explorations in art led eventually to the launch of a small magazine The Secret Alameda. And there's a business side to doing a magazine. This dawned on me by the second issue. And of course, ads are a big part of all magazines, minus the rare exception.

Would this magazine have ads? How about fake ads? That would be fun.

In the first issue of The Secret Alameda, there was an ad for "Bertram Eames, Esq. Purveyors of Fine Corinthian Leathers." The copy read, "We provide our discriminating customers with the traditional European elegance of distinction they require. Our professional staff persons will carefully consult with you to arrive at the properly elegant solutions for all your fine Corinthian leather needs, constantly hand-fitting you in the privacy of our lush, but traditional dressing chambers. Visit us in your fine town motorcars and enjoy our elegant premises reflecting the paneled libraries and sitting rooms of the best European manor houses of yore. Each and every fine leather product is crafted exclusively to traditional guild standards of centuries past, by appointment to Her Majesty the Queen, and perfected in the tradition of the finest French wines of distinction, premier cru. By appointment, or come in anytime between10 am to 10 pm."

And there was "Hongfeld and Twindler, Fine Art Consultants and Warehouse Liquidators—Chadwick Hongfeld and Horton Twindler, proprietors— We promise expert market positioning, a full range of semiotics [no license required] and unheard-of discount prices."

Such were the high jinks of, perhaps, a late-breaking adolescence. However certain developmental steps, as I came to reflect, simply could not be avoided. At some point, if the baseball hat has not been donned, and worn backwards, all personal growth is in danger of stalling.

High times. But now that I was publishing a magazine I began to discover the costs involved, and I quickly learned that having 88 subscribers at ten dollars apiece left a considerable shortfall. So this was what the business side was about. Need more subscribers? Advertise. Need more income, sell ads. For the first time in my life, I embarked down the road I'd regarded with such disdain -- and found it oddly bracing! It was as if I was finally getting it. I suddenly felt part of the main game. Free enterprise! Where had I been all those years?

Down from the [solitary] Mountain-and Mixed Metaphors.

I didn't like my magazine being called a "zine," but with 88 subscribers paying $2.50 for a sheaf of hand-stapled xerox pages, undeniably, it had those duck-like features. But it didn't need to be any bigger or slicker or more expensive. It possessed the one quality without which everything else hardly matters. It was my own duck-like creation. And that meant I could try whatever I decided to try. I decided to take up advertising. In that equation, if x be the true x, there are no small potatoes. If you're stepping across a line never before [personally] stepped across, it's a big step no matter how small it is!

Ontology without a PhD

Placing promo sheets under windshield wipers in the municipal parking lot behind the Courtyard Cafe and Gallery—that was my first advertising action. That's the moment I joined my fellow mortals in the rat race.

Of that first step across the line, I remember two things. The first had to do with writing the ad copy. I was inexorably drawn toward one particular phrase: blow-out sale. Hackneyed, yes. But isn't there something else, too? What exactly does the incantation blow out sale conjure?

The fun, it seems to me, is not that the items in question must leave the store in a great hurry, such a bargain as they are, but that the event is portrayed as explosive. Not just any explosive. And here's the fine point. It's the kind of explosive that clears out a problematic blockage, something impacted, cramped, held in, stultifying of circulation. In short, this is a blow out that rectifies. It clears the space, which is stifling and overstuffed. It opens. The blow out sale is an incisive solution, a return to health, celebratory. Present is a subtle invocation of the 4th of July where explosive devices are at their best, deployed for the sharp intake of breath at the sheer wonder of a starry blast lit against the night sky. The echo is there, only the blow out is now staged in broad daylight causing dollars to fly and merchandise to scatter happily in all directions. Such are the harmonic resonances of the blow out sale. And so, whatever else I might have written, this phrase had to be there. Without it, how could this first act of advertising link my former absence from mainstream business culture to this initiatory act of crossing over? Some low archetype had to be honored, but not without a little fine-tuned evidence of a higher level. The Secret Alameda was not secret for nothing. It existed for things laying beyond the world of blow out sales—something that eludes advertising by its very nature.

Slight detour: Blast Haus.

So taken was I by all this that I wondered if there could be an incantation even more powerful. What about BLAST? To blast was more than to blow out, true. Still, by itself, it wasn't enough. What about bringing in some German? BLAST HAUS. Now there was something! Not house, but haus. BLAST HAUS. Letting the phrase sink in, I noticed it incited a longing not so easy to put one's finger on. What kind of place would that be, a blast haus? Looking deeply, I could feel it. The special action that would occur inside the blast haus would be joyously violent, a total obliteration of THE OBSTACLE. The obliterating removal of everything that stands in the way. The only thing remaining would be an empty, open space—rapturously empty, and filled with a dream of pure beginning.

For awhile, I wondered if I should have called the magazine BLAST HAUS. But eventually I calmed down. I mean, Berlin, 1918, DADA… It wasn't where I was going. It was a dream of a difficult adolescence and at least part of me was already past that.

First Ad, part two.

The second thing I remember from that first ad was the furtive sense of illegitimacy that came over me in the parking lot while sticking those sheets under the wiper blades—the shifty feeling, the faint anxiety of my low behavior, a sense that punishment or embarrassment might intrude at any moment. Was this legal? No wonder I hadn't found my way into the robust life of commerce! Had instead taken refuge in abstruse reading, chess, and other strategies of keeping my distance. But for those same reasons, this action, the placement of sixty-seven advertisements under wiper blades, the public act, the proclamation of my own project!—for all those reasons, suddenly I felt the air around me, my feet on the ground. I was really standing where I was standing-on the sidewalk in the afternoon light, behind the old buildings facing Park Street. I looked out across the cars, the Beamers, Subarus, pickups, Peggy Williams' electric golf cart, the bicycle leaning against the light pole- all of them were present, too.

Reality Sets In…

I embarked on experiments of advertising the magazine. Over the next few years, I spent good money on ads in Utne Reader, Artweek and a few other publications. I traded ads with a few small magazines. I left magazines in airports, sent copies to media figures hoping for a plug, purchased a mailing list and briefly joined the army of bulk-mailers converting perfectly good trees into junk mail. I was getting my feet wet, a tyro. I was given much advice. Who is your reader? That was the first big trick in the bag. Who is your target audience? Retired English professors? Mid-level insurance exectutives? Got to know that. Next piece of expert advice: don't try writing copy yourself. That would be a big mistake! Trust the professional. For instance, here's a freebie. In any direct mail piece, always mention money back somehow. "Money cheerfully refunded if not satisfied." Like that. The professional knows the key buttons to push out there in the faceless herd.

Of course, I ignored the copy writing advice. And I've never been able to figure who my target audience is, either. So, right off, two big strikes against me. As my experiments continued, I began to observe that this advertising was not cost effective. Was I simply not doing it right? Not spending enough money? Surely, that part had to be true… But the magazine hadn't yet broken a hundred subscribers! It wasn't like I was competing with Ford Motors. Spending three or four hundred dollars on an ad equaled something like a third of the magazine's subscriber income! Was I producing an inferior product? But I kept getting good, earnest testimonials and even rave reviews! No, I was sure that couldn't be the problem, could it? No. But...? No, no…

Look here, I counseled myself. I think the magazine is great! But maybe I'm a fool. Let's say I'm not the best judge. So how bad could this magazine be? Would one person in ten thousand really connect? It couldn't be any worse than that! And in that case, the potential market in the U.S. would still be 30,000 readers! With my 88 subscribers, I could live with that! Yes, I could.

An Attack of Social Conscience

My own attempts to promote The Secret Alameda via advertising had not paid off, but there was another side to it. If no longer a buyer of advertising the prospect remained of being a seller of advertising. Wasn't that what magazines did? I should remind the reader that I describe conditions fifteen years ago. Still, pick up a magazine today. The ones that are still being produced are stuffed to the gillywhiskers with ads!

First, I turned to a few friends who ran small businesses. Peggy Williams, owner of the Courtyard Cafe and Gallery was first. It was like turning to mother. She bought an ad. I was mining the ore closest to the surface. Next I visited my schmooze-ready business acquaintances. Take the little coffee shop on Lincoln Avenue Vines. John was good for an ad. And then there was Thompson's Garden Center, right next door. Iris bought in. Kevin Patrick Books, down on Central Avenue was a place of utter perfection in terms of a certain dog-eared aesthetic. It was all used books, crammed into a small place with Kevin, himself, who was quiet, thoughtful and a bit untidy, as would be required. He was good for a small ad. And Paul's Newsstand—there was an anomaly. Only by stout resistance had a small band of right-thinking Alamedans been able to preserve the old fashioned, corner newsstand against the philistine forces of civic progress. Paul chipped in for an ad. Then up to The Sandwich Board. Sue, the Korean co-owner with her husband, chipped in. I always got their barbecued chicken [dripping with flavor] sandwich on a soft French roll, fully accessorized including the pepperoncini. This was a good sandwich! I even hit up an old friend in Oakland, Daniel Hunter, who ran a small photography business. He was in. But then I had to start doing some cold calls. There was a music store on Webster, Tom and Fud's. They looked a likely soft touch and, sure enough, Fud chipped in.

So it went, for a while. I liked these people. And slowly I began to think about these transactions. Although it wasn't too long before I crossed the one hundred mark in subscribers, what was it that I really had to offer these buyers of space on my pages? Would their outlays actually do their businesses one whit of good? As soon as I put the question to myself, I knew the answer.

No doubt these friends and acquaintances, and perhaps even some of the strangers, knew what they were doing—making a contribution, giving me a helping hand. No doubt, that's why the memories have stirred up such warm feelings. But something about the transaction did not feel right. It didn't feel so good. I was getting, but had nothing to give back.

Over the next three years, my experiments in advertising were producing increasingly clear results. Not only were they ineffective, but at some point about that time I first gave voice to the statement that spending my energy on selling ads was a soul destroying practice. I was surprised to hear such strong words escaping my lips. But as they sat there in the air, nothing moved me to revise them in any way.

Although my fantasy about how the right kind of ad in the right kind of place might be a powerful boost for my subscription list, that too had gotten pretty thin. My romance with advertising was just about over.

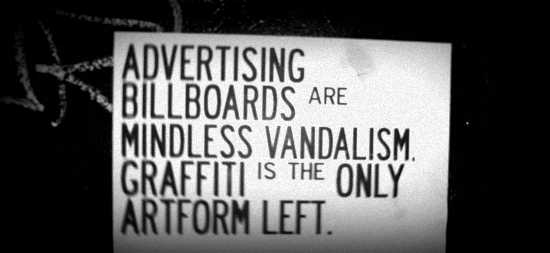

No more ads, I decided sometime in 1994—not without a little uneasiness at the abandonment of a revenue stream. But the last issue of The Secret Alameda, #8, ran ad free. What I began to realize as I paged through the issue, was how rare it was not to see any ads, nothing extraneous nagging at the edge of consciousness. Ad free space was almost like some kind of wilderness preservation on an interior level. I began to think that maybe my decision to abandon advertising had an aspect of social service to it that I hadn't realized. People who found these pages could breathe a little more freely. Their thoughts could roam without the annoying interference of a kind of noise.

Not too long ago the thought occurred to me that I could've gone further. I could have tried to set up my own advertising agency. I now had the perfect name for it: Zero Emissions Advertising. It would be a green certified business. None of its ads would produce any pernicious efluvia at all. No toxic outgassing so typical of other advertisers. No outgassing at all, in fact! These would be ads that did absolutely nothing. The Secret Alameda would continue, as before, on its own. Those who found it, would get there by some other route.

[works & conversations, which evolved from The Secret Alameda, has been a gift-economy magazine since 2007]

Posted by Richard Whittaker on Aug 11, 2009

SHARE YOUR REFLECTION

2 Past Reflections

On Mar 26, 2020 ahmed wrote:

The beer game is one of the games suitable for computers and suitable for Android operating systems and also the iPhone with a direct link, as the beer game is an old girl’s game that does not need great capabilities in your personal device or mobile phone as well as it does not require players to have any superpowers, the beer game download is It is characterized as an easy game and does not require great intelligence, so you can enjoy the game of beer and feel the excitement and excitement and there is no boredom at the time of playing

Download [View Link]

On Aug 11, 2009 Viral wrote:

Excellent piece! Loved reading it, and what a conclusion :-)

Thanks, Richard, for taking the time to share this wonderful story! I'm sure that it will have its ripples!

Post Your Reply