Karma Lekshe: Women In Spirituality

Listening to her speak is like sitting at high altitude, soaking in the clouds of compassion as they roll in with each breath. You can’t help but wonder how you got there or how the world could have looked anything less than the transcendent views that surround you now. What hits home about Venerable Karma Lekshe Tsomo is the sheer depth of her embodied humility, grace, and loving-kindness. And the colorfully human journey that brought her there.

Listening to her speak is like sitting at high altitude, soaking in the clouds of compassion as they roll in with each breath. You can’t help but wonder how you got there or how the world could have looked anything less than the transcendent views that surround you now. What hits home about Venerable Karma Lekshe Tsomo is the sheer depth of her embodied humility, grace, and loving-kindness. And the colorfully human journey that brought her there.

From a young age, she grew up surfing the waves of Malibu. At nineteen, she dropped out of college and, with surfboard in hand, stepped on a ship to Japan. From San Francisco to Honolulu to Yokohama, she rode the waves as a world-class surfer. When winter rolled around in Japan, she visited local monasteries and began to meditate.

Questions of life, meaning, and the ambiguity of death propelled her to keep pushing that envelope. In the 1960s, that inquiry brought her to study Buddhism at UC Berkeley, and later on, with Tibetan lamas in Dharamsala, India. When money ran out, she sold her guitar and stayed for anther year. Eventually, she found herself dedicating her life for that depth of study, service, and stillness, and in 1977, she ordained as a Buddhist nun to continue that path forward.

Such a “road less taken” journey has been witness to some incredible encounters. After being bit by a snake in the 1980s, she spent 3 months practicing equanimity at death’s door, not knowing whether she’d make it to the next day. Later that decade, she received a serendipitous gift offering and became an instrument for a groundbreaking global gathering that shed light on the setbacks of gender in spirituality. In the ripples that followed, she setup a education center for Himalayan women, aged 36 to 63, and watched them all learn to read within 2 months.

Beyond the content of her journey, the down-to-earth vibration of every word and story that flows through her is a teaching in itself.

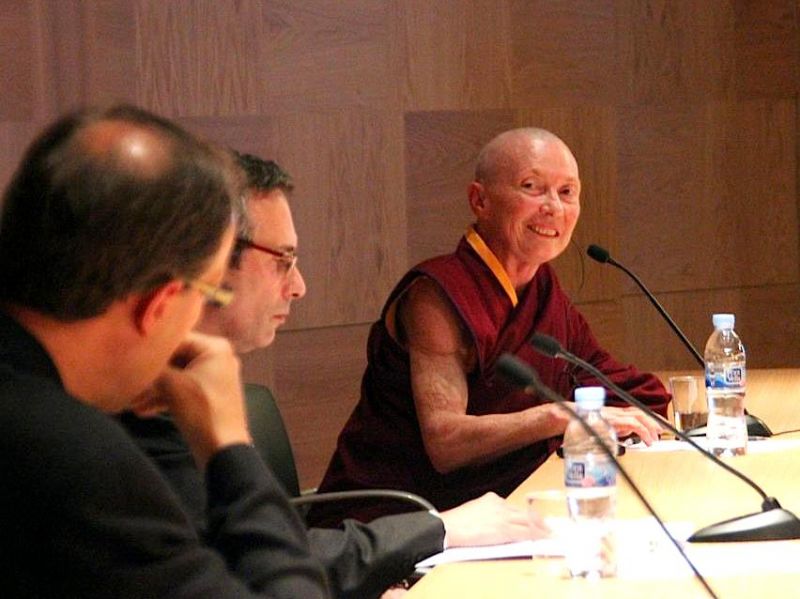

Last Saturday, she graciously accommodated our Awakin Call timetable and dialed in from Hong Kong at her local time of midnight, sharing with us until close to 2 am. All throughout, her tireless voice rang with a radiant joy that can light up even the most dormant sides of one’s being, and even from half a world away. In a soul-stirring conversation with Pavi and Amit, we learned about Karma Lekshe’s one-of-a-kind life trajectory—one imbued with both the lighthearted warmth and inner fortitude of ancient wisdom.

What’s in a Name?

It’s amazing how impactful a name can be.

“How did a Malibu surfer child you get to be where you are today?” Pavi asks at the beginning of the call.

“Well, It was sort of a birthright,” Karma Lekshe chuckles. “I was born into a family with the last name, ‘Zenn,’ so the kids at school used to tease me about being a Zen Buddhist. I didn’t know what that was, so I started to read about it.”

At the time, in the 50s—when there wasn’t much literature on Buddhism available in the United States—Ven. Lekshe found solace in the few books she found. Something about them stuck.

“I'd have all these questions as a kid about life and death and meaning,” she explained.

Her first vivid encounter with death happened as a young child on the Pacific Coast Highway. After losing two dogs to that treacherously busy road, she was puzzled with the impermanence of life:

“It really woke me up to the concept of suffering, and opened up a whole new raft of questions: Where did our dog go? I was really still quite young, so it was kind of a shock. That question of what happens to us after we die has followed me all the way through until today.”

Around the World on a Surfboard

At nineteen, she dropped out of Occidental College and boarded a ship to Japan, with surfboard in hand. After riding the waves in San Francisco, Honolulu, and Yokohama, when it started to snow, “I went to a monastery and started meditating,” Ven. Lekshe recalls. “I was searching for a teacher, which took many years to find.”

After a couple years in Asia, she ended up studying Buddhism at UC Berkeley, where she received a Bachelor of Arts in Oriental Languages. Then it was back to India, to Dharamsala, where at this point, the Dalai Lama had started the Tibetan library.

“The first day I had to start my classes, I ran down the mountain and burst into the classroom, and here was this little lama, sitting on a cushion at the far end of the classroom on the floor. He was explaining exactly what happens to us after we die. It was remarkable. So I sat at his feet for six years and learned everything that I could,” she recounts with an air of awe in her voice.

On Life, Death, and Meaning

For several decades since, Karma Lekshe’s inquiry on death has led to some incredible insights—both from Tibetan Buddhist teachings and through her own experience.

When Pavi asks, “What do you think is the power of living with a daily awareness of the reality of death," she doesn’t hold back:

“It wakes us up to the moment. We're often in denial about the reality of death, and as a result, we often waste away our precious moments. The Tibetan Buddhists say, "If we don't meditate on death in the morning, we waste the day. If don't meditate on death in the evening, we waste the night."

“So rather than think of death as something morbid, it's a way of recalling that our lifetime is limited. It's something that makes us conscious of the preciousness of each passing moment-- not just each passing day, but each passing moment. So that grounds us. It continually brings us back to the present, and we can be fully aware of each precious moment, instead of just spacing out and then we die.”

In her own experience, from a pre-teen caught in a stormy sea to the nature of spending summers in the Himalayas, she’s had her fair share of moments to remind her of the gift of life, and our quality of attention through it.

At the age of 11 or 12, she and her brother had gone swimming and were caught three-quarters of a mile offshore in one of the biggest storms that hit Malibu. Diving under one wave after the next, and hanging on to kelp, she recalls:

“And we made peace with not only the situation, but with each other. Two kids that grew up together, and then, it was really like facing death head-on. And it was quite terrifying. It was also quite beautiful.”

Eventually, a neighbor on shore who’d seen them head out had called the Coast Guard, and after a couple of hours, they were picked up by a U.S. Coast Guard ship. But the impact of that learning was deeply ingrained.

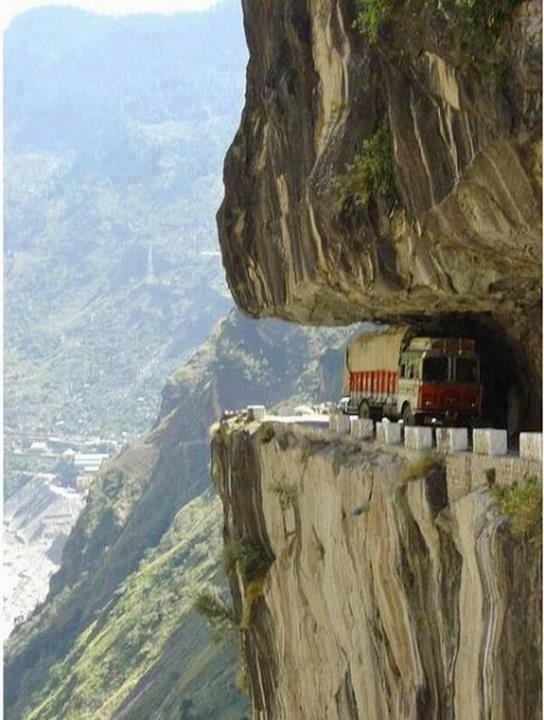

Years later, she came to live in the Himalayas, where the precariousness of life greets you at each corner.

“You go over these treacherous roads,” she describes. “Busses regularly go over the edge. Jeeps crash and burn. Or get caught in avalanches. We’d go through war zones where anything can happen. You just ask the guard, “Is there shooting ahead?” and if there is, you just travel by day.”

“You go over these treacherous roads,” she describes. “Busses regularly go over the edge. Jeeps crash and burn. Or get caught in avalanches. We’d go through war zones where anything can happen. You just ask the guard, “Is there shooting ahead?” and if there is, you just travel by day.”

One of the closest calls was when she was bitten by a viper while walking in the forest in Northern India. She hadn’t seen the snake, but by the time she made it back to the monastery, she knew something was terribly wrong.

“The next morning, a Tibetan doctor found the bite. He couldn’t immediately recognize what it was—it could’ve been a spider or scorpion or a snake, but he immediately raced off and got some special medicine. The Tibetans have really good medicines for poisons. I took that immediately.

“I had never seen this doctor do something like that—diagnose, then race off himself to get the medicine and bring back a glass of water to take it right away. So I guess it was a pretty critical moment there. I think that it must have saved my life, because usually people get bitten by a viper and they die immediately. In this case, I didn't die instantly, but got gangrene, because there were no proper hospitals in the mountains there. Eight days later, by the time I got to a proper hospital in Delhi, the gangrene was really serious.”

For three months, she was in the hospital, not knowing whether she’d be alive tomorrow. There was nothing else she could do but cultivate.

“Even though I had already been meditating for many years at that time (thanks to my last name Zenn), whether I was meditating or just spacing out, I'm not completely sure. But I fancied I was meditating. But it’s not so easy to concentrate when you’re in a life-or-death situation where you’re in great pain. I figured I was in pretty good shape. I was ready to die, but I never factored in the pain that you might face. Some people might be lucky and pass into the night with no pain, no discomfort. But we can't guarantee that.”

Eventually, she made it through, with gratitude for the lessons that experience gave her: “I mean, you understand the power of loving kindness. You recognize how utterly dependent we are on other beings. And so many things, like experiencing impermanence up close and personal.”

Women in Buddhism

The 20th century has been witness to radical shifts in the role of women, and monastic orders are no exception. For Karma Lekshe, stepping into life as a Buddhist nun in the 1970s was a blessing that came with its own set of constraints. At that time in India, there were many monasteries where men were able to train, study, and practice as monks. After the communists took over Tibet and the Dalai Lama, along with 100,000 refugees, fled to India, they immediately set about establishing monastic centers in India. Today, there are 300 monastic centers there.

But for women, there are very few. And in those days, there were none.

“The monasteries were always the learning centers in Tibet, and in most Buddhist societies. And those great learning centers were not open to women. Women were systematically excluded from them. So it meant that once my male classmates learned Tibetan, they could go down to South India and just check in to one of these amazing monastic learning centers. But there was no place for me to go.

“The monasteries were always the learning centers in Tibet, and in most Buddhist societies. And those great learning centers were not open to women. Women were systematically excluded from them. So it meant that once my male classmates learned Tibetan, they could go down to South India and just check in to one of these amazing monastic learning centers. But there was no place for me to go.  Women were not welcome there.

Women were not welcome there.

"I remember very clearly asking my teacher, "Well, why don't I just go down to Sera Monastery?”

"And he said, "You wouldn't be happy and they wouldn't be happy."

"There really was no place for women, so eventually we had to start our own monastery. That's one solution."

A Serendipitous Offering

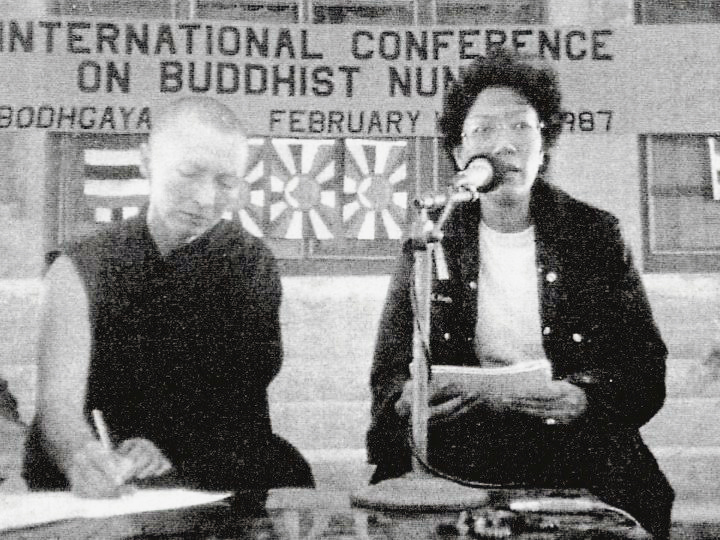

With such deeply entrenched gender divisions— and her own lack of encouragement, facilities, and opportunities as a Buddhist nun—in the late 1980s, she and a group of other women and nuns decided to convene a gathering to explore these misalignments. And the first donation towards it came almost by accident.

In the middle of the night, Karma Lekshe heard a thick Texan accent calling outside her mud hut: “Help, help! Help me, I’m lost!”

She went out, found the lost visitor, and led her back to her hotel. The next day, they ran into each other in the village, and she started telling her about the idea for a gathering on women in Buddhism.

"I think it's a great idea. When are you going to get together?" the Texan woman asked.

"Oh, January."

“How much money do you have for putting that conference on?"

"Well, we don't have any."

"Oh! What if I lend you $5,000?"

“Well, you don't even know me."

"I know you."

"That's very kind of you, but what if the conference is not very successful and we can't pay back the money?"

"Then we'll call it a gift."

The conditions had aligned for that first Sakyadhita Conference to be set in motion. It attracted several hundred people, and the opening ceremony with the Dalai Lama was witness to a crowd of 1,500.

“And, you know, it was something really new. People didn't really know what we were doing. Some monks found it quite threatening to see all these women getting together. It was in Bodhgaya, in a very poor village, and we put on a Sangha Dana (a lunch offering) for all the abbots in town, which are, of course, all men. We had about 100 people sitting down at the same table as nuns. Oh, that was very groundbreaking. There were so many groundbreaking things. Like nuns welcoming the Dalai Lama playing the traditional horns,” Venerable Lekshe illustrates.

“After a week of our discussions and a week-long tour to the Buddhist sacred sites, we did all the accounting, and it turned out we made our expenses exactly, and were able to repay the $5,000."

From this first conference birthed several beautiful initiatives—from a recurring conference every 2 years to the establishment of Sakyadhita (which means “Daughter of the Buddha”) as an international association of Buddhist women to the Jamyang Foundation, a network of 15 learning centers for nuns, laywomen, and children to grow both academically and spiritually.

“We’ve continued since that first conference, with very little support on the financial side,” she states, “but lots of encouragement and inspiration from all these wonderful women. In particular, there are also a lot of male allies. That's been very important.”

And all of it is done as a labor of love—all of it for the benefit of many.

Far Beyond Her Own Existence

From her stories, it sounds as if it all flows so effortlessly, like nature simply unfolding through her life. But in the unspoken details, you can glimpse how much work, dedication, patience and cultivation it takes to keep all the threads together.

From hazardous Himalayan living conditions to minimal funding to the rigorous schedule and spartan nature of monastic life—it’s clear that a journey like Venerable Lekshe’s is one lived entirely in service to something far beyond her own existence. Between coordinating international conferences and 15+ schools in the Himalayas, Bangladesh, and Laos, she serves as a professor of Theology and Religious Studies at the University of San Diego and still makes time to share stories on our Awakin Call in-between travels at midnight.

From hazardous Himalayan living conditions to minimal funding to the rigorous schedule and spartan nature of monastic life—it’s clear that a journey like Venerable Lekshe’s is one lived entirely in service to something far beyond her own existence. Between coordinating international conferences and 15+ schools in the Himalayas, Bangladesh, and Laos, she serves as a professor of Theology and Religious Studies at the University of San Diego and still makes time to share stories on our Awakin Call in-between travels at midnight.

With a life like that, she becomes an instrument for things far greater to flow through. One such instance is in her efforts to establish opportunities for women to fully ordain as a Tibetan nun.

“The Tibetan tradition doesn’t have a lineage for full ordination for women. We have to go to other traditions. I went to Korea for full ordination,” she explains. “The problem is the technicality of monastic law—how to get the thing started.”

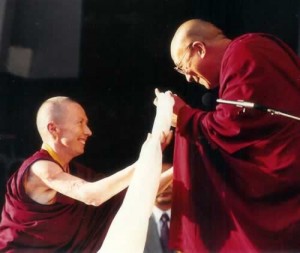

One particular ally and teacher in this has been His Holiness the Dalai Lama. After winning a Peace Prize in Switzerland, where he was gifted 50,000 Swiss Francs, he gave the money to Karma Lekshe and told her, “I want you to meet and figure out a way to get this done.”

One particular ally and teacher in this has been His Holiness the Dalai Lama. After winning a Peace Prize in Switzerland, where he was gifted 50,000 Swiss Francs, he gave the money to Karma Lekshe and told her, “I want you to meet and figure out a way to get this done.”

“He asked us to form a committee. We were five western nuns… So we’ve been meeting for the last 8-9 years, and doing the research on trying to find a method that would be acceptable, even to the most conservative of the senior monks. I'm quite confident that we will be able to establish full ordination for women, and actually, it's a religious rite. If women don't have equal religious rites, then they don't have equal human rights. That's just logical. So, we're working on it,” she explains, with a light chuckle in her tone.

Buddhism, she explains, invite us to check our motivation: Why are we living? What’s the purpose of this life? In some Buddhist traditions, the idea is to achieve liberation, not only for one’s personal benefit, but in order to relieve the suffering of others.

“I find this a useful measure,” she shares. “Why am I doing this? Am I doing this for my own, limited personal interest? Or am I doing it for some greater purpose? … What we find is that the wider our compassion—the more people we let into our sphere of interest—the happier we get. My experience has been that people who are most concerned about themselves are the most miserable. And those who are most concerned about others, and doing something about it, are the happiest. So maybe they’re on to something.”

“I find this a useful measure,” she shares. “Why am I doing this? Am I doing this for my own, limited personal interest? Or am I doing it for some greater purpose? … What we find is that the wider our compassion—the more people we let into our sphere of interest—the happier we get. My experience has been that people who are most concerned about themselves are the most miserable. And those who are most concerned about others, and doing something about it, are the happiest. So maybe they’re on to something.”

Whether Venerable with a capital V, or Professor of Theology, or Zenn child, Karma Lekshe’s wide range of roles and relations is a reflection of the expansive spirit with which she lives.

“We’re all interconnected, right?” she reminds us at the end of the call. “None of us could live independently from each other. We tend to put things in different compartments, but it’s all interconnected.”

From the simple surfer girl settling into the sweeping silence of the landscapes to the recovering patient witnessing impermanence at death’s doorstep, or the Buddhist nun convening women for spiritual growth across time and space, Karma Lekshe beams a presence that cuts to the core of each waking moment.

In the last moments of the call-- after a collective group “thank you”—there was a brief silence on the line, followed by a deep, hearty sigh and light, radiant laughter from Karma Lekshe. It was as if the echoes of her heart had stretched into the airwaves, elevating everyone on that frequency to see a little more deeply, love a little more fully, and feel the totality of the miracle of existence with each simple breathe we take.

Posted by Audrey Lin on Mar 26, 2015

On Mar 27, 2015 Nisha Srinivasan wrote:

Post Your Reply