The Aborigine And His Land

I was in Sydney recently, and after 2 days of touristy stuff in Circular Quay, I was yearning for a deeper connection to the land. We had a day and a half to go, and my friend said, "Isn't this amazing? There's so much to see here." I found myself sharing my deep yearning to understand the aboriginal culture.

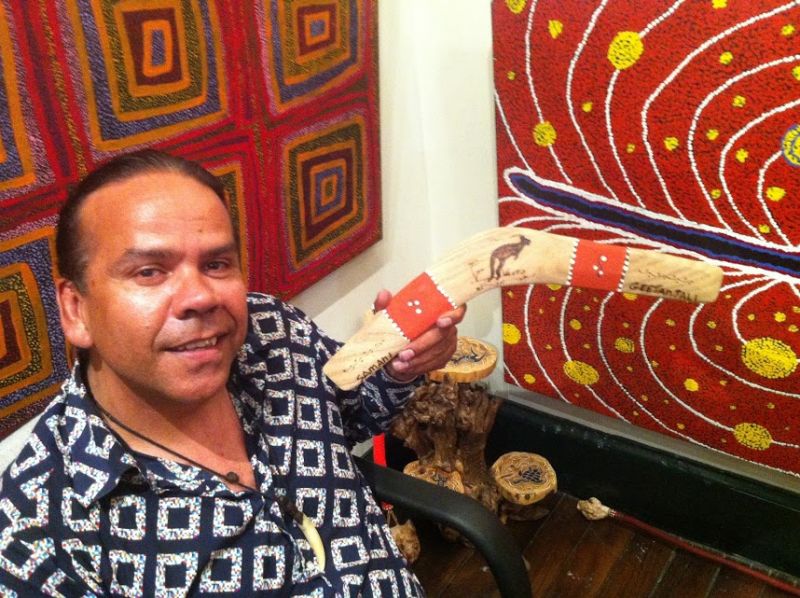

And then, just as my sentence finished, I stopped in my tracks. An amazing painting had caught my eye. This was not a landscape in a pricey gallery (we had passed a couple of those). There was something else here that had hooked me. Looking in, I found an aborigine working away wood-carving a didjeridoo. My friend and I exchanged looks, and we knew we had to go in.

What followed was an amazing conversation. It was the first day of this shop and the proprietor was setting up. Already, people had walked in and given him orders to fulfill, and there he was, wood-carving a didjeridoo for someone, totally relaxed, and welcoming us as an honored guest into his home. The didjeridoo is such an amazing instrument, completely hollowed out by termites. It takes special eyes to discover music in the work on nature. As we took in the gorgeous paintings on display, I asked him, "What do these mean?" He replied, "Oh, these are actually maps of our land. The round patches designate water holes. The squiggly lines are mountain passes. Before we had cameras in the sky, this is how our people told the next generation about their land."

Can you imagine getting out of our utilitarian mindset to look at a map as a work of art? Can you imagine capturing the impression our land makes on our soul and leaving that behind for future generations? The poetry of that thought fascinated me.

I asked my new aboriginal friend, "How do I ask - 'what is your name?' in your language?" He looked puzzled and could not answer. Then he said, "We actually don't ask that question. When we have decided to welcome you, your name is irrelevant. I got my name much later in life, when I was 28."

Wow!

As to his name, he said, "I am called Yarramunua, the man who protects the river." Even names have strong connections to the land. I asked him about the local cuisine - what do the aborigines normally eat? Barramundy (a local fish) and rice. They also eat other meats, like the kangaroo and the emu. And it turns out that the boomerang was used as a weapon to break the kangaroo's leg. For all the meat-eating, the aborigines understood the sanctity of life, even of the animals they ate. Nesting places were considered out of bounds, and only when the animal had matured would they be hunted for food.

The aborigines placed a lot of emphasis on respecting the wisdom of elders, and Yarramunua had a bizarre story to illustrate his own initiation into that culture. As a young lad, he wasn’t much into listening to anyone. So when his grandfather told him not to enter the river as it was full of crocodiles, he did exactly that. And then, a crocodile came and bit him in his thigh and started dragging him in. At that moment, his grandfather, who was hiding and observing, came running out and killed the crocodile with his spear. As a keepsake, he gave the young lad a tooth of the crocodile, to remind him of the value of elder wisdom. Yarramunua said, “After that day, a part of my brain just shifted. It was no longer an intellectual decision to listen to elders.” Yarramunua carries that tooth around his neck to remind him to be grateful for the wisdom he has received from his elders (see picture below).

Other amazing things about Yarramunua - he cannot read or write in the manner that we can. He identifies letters and can copy them for his engravings, but that is as far as he can go. And yet, when he communicates, he goes far beyond many men of letters that I have met. His little shop in Circular Quay promotes the work of his people and we were quite surprised by how affordable it was - he has a mission to bridge cultures and help regular people (not just the affluent) experience the aboriginal culture. After many fascinating conversations with us, I decided to tag him with a Smile Card, and paid forward a boomerang. As I explained the concept of the smile card, he said, “You know, we do this all the time in our community. In fact, I gifted a boomerang today to a kid - just felt like it.” I replied, “Yes, I know this is normal in your culture. This tag is not for you, but for me (to feel like I could be a little part of your journey).”

I asked him about time, "I've heard that the aborigines don't really have a concept of time, as in the past or the future." He replied, "Yes, that is correct - our culture focuses on the present moment." He exemplified it with the ease with which he sat and chatted with us, while working away, without losing his cool. He was carving an intense piece and I asked him how he was doing it. He shared that he did it without thinking- the art just flew through him. It was also fascinating to see that he did not confine himself as an artist or a musician - he did both with ease.

We ended with hugs, and I felt privileged to receive a taste of indigenous, yet universal values, right at the heart of touristy Circular Quay in Sydney.

Posted by Somik Raha on Feb 28, 2013

SHARE YOUR REFLECTION

3 Past Reflections

On Mar 3, 2013 Conrad wrote:

On Mar 1, 2013 Lavanya wrote:

Post Your Reply